A 1908 Great Race GalleryClick to view full-size images, click on the enlargement to close it. | ||

|

|

|

|

|

|

| These images are from the National Archives. Lots more to come! | |

It originally appeared in the December 1978 issue. |

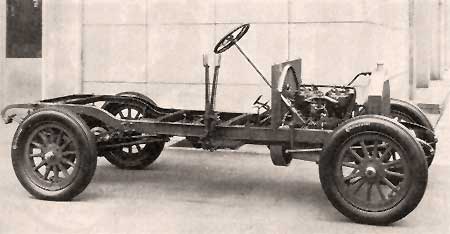

This is the way it looked on Feb. 12, 19O8 when six automobiles lined up for the New York to Paris race. The cars included a DeDion, a Motobloc, |

New York To Paris —

|

[Ed: December, 1978] Bill Harrah, the Reno tycoon, died a few months ago owning a vast array of casinos, hotels, airplanes, land and other property. But the items of his $137 million estate that he prized most were his 1,500 beautifully restored old automobiles. And his favorite of these was a gray 1907 Thomas Flyer. This was the winning car in the longest auto race in history, the incredible 1908 New York-to-Paris competition. This never has been duplicated. After 70 years it is still considered by many to be the most extraordinary event in automobile history. The year before there had been a Peking to Paris race across Asia and Europe won by Prince Scipione Borghese in an Itala car. Two French cars, both De Dions, followed. Le Matin, a Paris news paper, sponsored this race. Looking for new glory it planned an around-the-world event and enlisted The New York Times as co-sponsor. Somebody in Paris drew a line on a globe. Though paved high ways were still in the future, contestants would drive from New York to Chicago, go across Canada to Alaska, down the frozen Yukon River, across the Bering Strait, then through Siberia and Europe to Paris. Canada promptly announced the impossibility of that part. The route was revised to send the cars from Chicago to San Francisco, thence by steamer to Valdez, Alaska. They would drive from there to the Yukon. To be sure of ice on the river, the race had to be in winter. Though no car then had been driven across the U.S. in winter (and only seven in the summer) the start from New York vas set for February 12, 1908. Tires were fragile and cars frail but six showed up. Three were French — a De Dion, a Motobloc and a tiny Sizaire-Naudin. There was an Italian Zust, a German Protos, and a single last-minute American entry, the $4000 Thomas Flyer, made in Buffalo, N.Y. The Sizaire-Naudin had a single cylinder, The others were four- cylinder machines. All had right-hand steering, then customary. A screaming, cheering Lincoln’s Birthday crowd of 250,000 jammed the Times Square area for the start up Broadway. Present was Peter Helck a schoolboy crazy about autos who later became a famous painter of racing cars. Rex Beach, the novelist who had been in Alaska, also was in the crowd. He bet $1,000 that not a car would finish. |

Besides 20 mostly fur-garbed men, the cars carried American flags, hampers of food and drink, sleep gear, spare parts, extra gasoline tanks, searchlights, lanterns, chains, ropes, planks, picks and shovels, some even firearms. The weather was clear and around freezing when a shot from a gold-plated pistol started the race and the Sizaire-Naudin with Auguste Pons at the wheel, led the cars out of Times Square. But shovels were soon needed. Albany was the first day’s goal via what is now Highway 9 but beginning at Yonkers thawing snow “transformed a naturally unsatisfactory highway into a veritable quagmire.” Despite chains, car after car became stuck. “I will win,” said a Frenchman, “I shovel very hard.” The Zust led at first, then the Thomas. These and the De Dion made the 116 miles to Hudson through snow drifts and stopped for the night. The Protos was at Poughkeepsie. Mishaps stopped the Motobloc at Peekskill. It never caught up and eventually quit the contest. Pons and the Sizaire-Naudin were out of the race two hours after the start. The rear axle of the little car collapsed climbing Spitlock Hill and replacement parts didn’t work. But Pons is remembered. His daughter, Lily, became one of the greatest opera singers. The other four cars, all of 30 to 60 horsepower, battled ahead. Driving the Thomas was Montague Roberts, 25, a race driver and demonstrator for the Thomas New York Dealer. With him as “mechanician” was George Schuster, 35, a stubborn German- speaking test driver from the Thomas factory and T. Walter Williams, a New York Times reporter. G. Bourcier St. Chaffray, an aristocratic Frenchman who wore white, was captain of the De Dion. He also was “Commissionaire General” for Le Matin. Besides a French mechanic, St. Chaffray had with him Capt. Hans Hendrik Hansen, a Norwegian explorer who couldn’t drive but knew the Arctic. Lt. Hans Koeppen, 31, a determined six-foot officer on leave from the German General Staff, was in charge of the Protos and correspondent for a Berlin newspaper. He had several drivers in the course of the race. Giulio Sirtori drove the Zust with Henri Haaga, mechanic, and Antonio Scarfoglio, a young newspaper correspondent. |

The Zust, the Protos and the De Dion lined upon Broadway, |

|

The Zust led for a time but the Thomas was first into Buffalo. There an additional mechanic, George Miller, was assigned to the car. Factory men worked all night substituting a straight axle for the front drop-axle that scraped snow. Blocks were put on top of the axles for more road clearance. The De Dion was overhauled similarly by the Pierce-Arrow plant. It was first to Erie, Pa., but the Thomas was ahead into Cleveland and Toledo. The racers ran into a blizzard. Farmers made money pulling them out of snowdrifts with teams of horses. One day in Indiana the Thomas floundered only eight miles. With roads impassable, the Americans drove into Chicago over Lake Shore Railroad tracks on Feb 25th. The Thomas increased its lead in the mud of Iowa and it was at Carroll, Iowa, that the luckless Motobloc quit the race. Schools sometimes were dismissed to allow children to see the cars. A newspaper termed the racers “fierce-looking, wild-eyed men who travel without sleep and without food.” At Omaha, Captain Hansen, who quit the De Dion in Chicago, joined the Thomas. Cowboys, cowgirls and a band welcomed the flyer in Cheyenne, Wyo. There a westerner, E. Linn Mathewson, only 21, took over the driving from Roberts who had to return east to keep racing dates. With deep snow blocking the road, Mattewson obtained permission from the Union Pacific to bump over its tracks through the Aspen Tunnel to Evanston, Wyo.., and later from Wahsatch to Castle Rock, Utah. The Thomas damaged the roadbed so badly that the railroad refused this to the following cars, increasing further the lead of the Thomas despite many repairs. When Harold Brinker, another 21-year-old, drove it into San Francisco on March 24, the Zust was in Utah and the De Dion and Protos still in Wyoming. |

At San Francisco, Schuster was made captain-driver of the Thomas. After repairs it was shipped by steamer to Seattle, where George McAdam, a New York Times man joined, then in a second steamer to Valdez, Alaska. There snowdrifts as high as houses prevented it being driven off the dock. It was shipped back to Seattle. There Schuster learned the race was to be resumed in Vladivostok; that the Zust and De Dion which followed him into San Francisco, were enroute there by way of Japan; that the Protos, which had been shipped by rail to Seattle from its last breakdown near Pocatello, Idaho, was being sent direct to Vladivostok. Schuster chose to go by way of Japan. At this point, the Race Committee gave the Thomas a 15-day advantage for going to Alaska and penalized the Protos 15 days for not driving to San Francisco. This proved important. As all four cars reached Vladivostok, three of them after 350 tortuous miles across Japan, the Marquise de Dion, maker of the De Dion car withdrew it. In a frantic effort to stay in the contest, St. Chaffray attempted to buy all the gasoline available in the area and trade it for a seat on the Thomas or the Zust. Both crews refused him and found other gasoline. Koeppen and two experts from the Protos factory, Robert Fuchs and Casper Neuberger, overhauled the German car and stripped it of every ounce of excess weight. While the Zust was delayed further, the Protos drove west from Vladivostok at 8 a.m. May 22, a rainy day. The Thomas followed two hours later. The cars traveled, MacAdam wrote, “out into a dismal flat, rain- drenched country, over or rather through a road that was a streak of mud far as the eye could reach.” Both had chains on the rear wheels. |

The Zust, the Protos and the De Dion lined upon Broadway, |

In Williamsville, near Buffalo, N.Y., the Thomas drew some spectators as the crew repairs a tire. (Photo from book “The Longest Auto Race” |

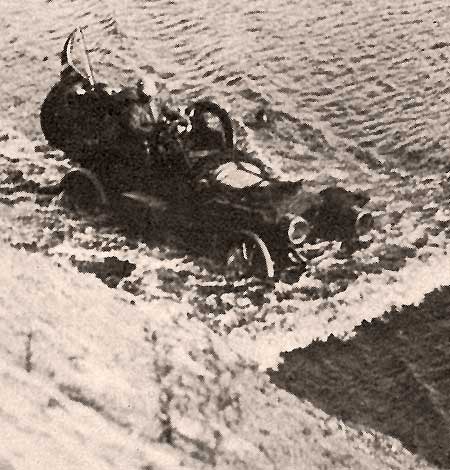

Twenty miles out the Thomas caught up with the Protos stuck in mud so deep that only the tops of the rear wheels showed. The three Germans and a Russian officer guide were trying to move it but as the wheels churned it sank deeper. “Let’s help them,” said Hansen. Schuster stopped the American car. Miller passed the Germans a towrope and the Thomas pulled the Protos to solid ground. By way of thanks for what he called “a gallant, comradely act,” Koeppen uncorked a bottle of champagne and poured drinks. MacAdam photographed the rescue and Peter Helck the artist, later recorded it in a famous oil painting now in the Harrah Collection in Reno. To escape the mud, both cars soon were bumping along the Trans-Siberian railroad tracks. This stripped gears and made the drivers nervous wrecks but they kept going. On the road the Germans and Americans passed and repassed each other. The Thomas was delayed twice for five-day stretches while Schuster went ahead for spare parts. Although the Thomas led for days at a time, the Protos collected $1,000 from the railroad for being first at Chita and another $1,000 from the Imperial Automobile Club of Russia for being first to reach St. Petersburg. It eventually reached Paris four days ahead of the Thomas. But because of its advantage for going to Alaska and the penalty against the Protos for not crossing America, the Thomas was the winner by 26 days. It had traveled 13,341 miles in 169 days when it reached Le Matin at 8 p.m. on June 30. The Zust reached Paris Sept. 17. George Schuster and his crew, along with Montague Roberts, received trophies and a big reception in New York and were congratulated by President Theodore Roosevelt at Oyster Bay. Schuster was supposed to collect $1,000, but never did, from an official of the Automobile Club of America for carrying one of its flags to Paris. Schuster did receive a $1,000 bonus from E.R. Thomas, head of the company, and a promise that “as long as there is a Thomas company, you and Miller have jobs.” |

Unfortunately the next Thomas models were lemons and the company went bankrupt in 1913. Schuster then worked for Pierce-Arrow and was a Dodge dealer in Springville, N.Y. In 1964, Bill Harrah brought the remains of the winning Thomas Flyer from the Long Island Auto Museum and had Schuster and his son, George Jr., come to Reno and advise on its restoration. A wild Warner Brothers film, “The Great Race,” and a book by Schuster recalled it in 1965 and 1966. In 1968, a reliability tour organized by Millard Newman, a Tampa, Fla., cigar manufacturer, who drove a 1911 Rolls-Royce, celebrated the 60th anniversary of the famous race by retracing the U.S. part under the auspices of the Veteran Motor Car Club of America. The Thomas Flyer of the original race went along on a trailer and was displayed at stops. Of 38 pre-1915 cars that left New York on June 16, 32 arrived in San Francisco on July 13. Warren S. Weiant, Newark, Ohio, won a New York Times Trophy in a 1909 Simplex. Next was Thomas J. Lester, Cleveland, who drove a 1909 Chalmers Detroit. Dr. Montague Roberts, a New Jersey surgeon and son of the 1908 race driver, was seventh in a 1911 Abbott-Detroit. George Schuster, by then 95 and blind, at the Buffalo stop of the rerun received from the New York Times the $1,000 due from the auto club 60 years earlier. With Bill Harrah at his side, he sat again behind the wheel of the old Flyer. Schuster died at 99 on July 4, 1972, in a Springville, N.Y., nursing home. Roberts died in 1957 and Koeppen was killed in World War 1. A reverse rerun of the whole race was planned as a bicentennial event. But even messages from Vice President Nelson Rockefeller and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger failed to gain Soviet approval. Instead Steven Potash of Cleveland arranged a 1976 reliability run from Istanbul across Europe and the U.S. to San Francisco. Russell Benore, Toledo, Ohio, won this in a red 1912 Detroit-Abbott; followed by Edward Schuler, Morriston, Ind., in a 1914 Dodge; and a 1911 T Ford driven first by Dr. P. C. Kesling and then William F. Wooke, LaPorte, Ind. |

Held by the Deutsches Museum, Munich, Germany, |

The Protos being pulled from the mud in Siberia by the Thomas Flyer. |

|

Peter Helck the artist who lives in Millerton, N.Y. every February 12th, anniversary of the start of the race, as he did for their fathers, sends greetings to Dr. Montague Roberts and to George Schuster Jr., the latter an insurance man at Baldwinsville, N.Y. |

While the Thomas Company did not prosper as a result of the race, the American automobile industry did. “Considering the roads, season, weather, and difficulties of making such a trip at that period,” wrote James Rood Doolittle later in his book The Romance of the Automobile Industry, “the fact stands out as the most brilliant example of the publicity stunt ever carried through in the automobile industry... that three automobiles were able to run from new York to San Francisco in winter, shed new light on the sturdiness and power of the motor car. |

Moving from Nebraska across the northeast corner of Colorado, then back into Nebraska, the Thomas became mired in the mud near Julesburg, CO |

Additional photographs of the “New York to Paris” race, including pictures of the late George Schuster, driver of the winning Thomas Flyer, appear [below]. |

In Manchuria, using a railroad track for a road, the Thomas was halted temporarily by a bridge which had the cross ties too far apart for driving. |

In Siberia, the Thomas drives along a flooded river road. |

The sad-looking Thomas Flyer as it appeared |

Fifty-six years after the historic race, George Schuster sits behind the wheel of the Thomas Flyer in Reno, Nev. (Photo Credit to Western History Research Center, University of Wyoming) |

In this 1964 photograph, George Schuster (now 91) was in Reno to advise |

This is the 1907 Thomas Flyer following restoration by Harrah’s Automobile Collection, Reno, Nev. The car was restored to the condition in which it appeared at the end of the race. |